Enumclaw's Early Plateau Neighbors

When you think of the Enumclaw Plateau, that vast flatland between the White and Green Rivers and extending from the Cascade foothills to where it drops off at Muckleshoot, what other towns come to mind? Well, there aren't any. Only Enumclaw. But there used to be other settlements, several older and several bigger. The Plateau between the rivers was once a whole network of communities. Who were they and where did they go?

With the opening of the Naches wagon road, after a few false starts, settlers started trickling in to the Enumclaw Plateau. After Allen Porter left, others soon came and some stayed. The early wagon roads were widened trails--one way with turnouts for passing. Trees were cut, but the stumps remained. Other pioneers had no roads at all--they walked in on rough paths. With very limited transportation, several settlements sprang up in relatively close proximity, but for different reasons. Some developed as small communities of farmers, while others began (and ended) as coal-mining towns. Among these communities were post offices, schools, general stores, hotels, and mills. But in time, as transportation and economics changed, they became simply crossroads or were abandoned altogether.

Seven years after the Puget Sound War, Congress passed the Homestead Act to replace the Donation Land Act. A person could now get 160 acres of free land by filing a claim, living there for five years, and making improvements. In 1870, James McClintock was the first to do so in our area, settling near what is now Evergreen Cemetery. He eventually established a large dairy and built a 15-room roadhouse for his family and travelers.

In 1870, Johannes Mahler built a cabin about a mile from McClintock, near the current Mahler Park, which he eventually donated to the people of Enumclaw. He planted potatoes and hired out his team of horses for road building and transporting pioneers and their supplies. George Vanderbeck arrived with Mahler and settled near Boise Creek.

In the years to come, many homesteaders tried to eek out a living in the Plateau wilderness. Several succeeded in establishing successful farms and mills, but others gave up their claims, overwhelmed by the difficulties faced in this remote place. John Templeton, James Shorley, Charles Clark, and Peter Sanders all filed claims and then left by 1874. Those coming later often used their abandoned cabins until more suitable living quarters could be erected.

Boise Creek

The first settler at Boise Creek area was George Vanderbeck, who accompanied Johannes Mahler to the Plateau in 1870. His wife and baby from Chicago soon joined him, to become the first white family in the area. Their claim extended to where Enumclaw High School now sits and near where an Indian longhouse was located then. A few months later, Henry Grothen and his family joined them.

James Johnson, his wife, and five of their twelve children moved from eastern Canada to a spot near the confluence of Boise Creek and the White River in 1875. After James put a cabin together, he built a flour mill and dam to power it. He also operated a ferry across the White River. This wasn't your ordinary ferry, but a small rowboat following a cable across the rapids. With no Mud Mountain Dam to control the flow, the crossing was often very dangerous. The boat often capsized, and several pioneers, including four mailmen, drowned. Horses and other animals had to swim, and many of them were lost also.

As others began moving in, George Vanderbeck anticipated that the settlement would flourish once the railroad came through, so he platted part of his homestead as a town in 1888 and established a post office the following year. His prediction came true when the Northern Pacific Railroad ran its main line through there and built a trestle across the White River bridge to Buckley. The town became a flag station, where trains stopped if the flagman raised the flag; otherwise, they passed on by. By this time, Boise Creek boasted a school, two general stores, a hotel, a sawmill, a shingle mill, and a saloon.1

The community also got a log bridge over the river, rendering the ferry obsolete. After it was destroyed by flooding in 1906 and again in 1911, a new steel bridge was built, which was also destroyed by flooding.

With the opening of the Naches wagon road, after a few false starts, settlers started trickling in to the Enumclaw Plateau. After Allen Porter left, others soon came and some stayed. The early wagon roads were widened trails--one way with turnouts for passing. Trees were cut, but the stumps remained. Other pioneers had no roads at all--they walked in on rough paths. With very limited transportation, several settlements sprang up in relatively close proximity, but for different reasons. Some developed as small communities of farmers, while others began (and ended) as coal-mining towns. Among these communities were post offices, schools, general stores, hotels, and mills. But in time, as transportation and economics changed, they became simply crossroads or were abandoned altogether.

Seven years after the Puget Sound War, Congress passed the Homestead Act to replace the Donation Land Act. A person could now get 160 acres of free land by filing a claim, living there for five years, and making improvements. In 1870, James McClintock was the first to do so in our area, settling near what is now Evergreen Cemetery. He eventually established a large dairy and built a 15-room roadhouse for his family and travelers.

In 1870, Johannes Mahler built a cabin about a mile from McClintock, near the current Mahler Park, which he eventually donated to the people of Enumclaw. He planted potatoes and hired out his team of horses for road building and transporting pioneers and their supplies. George Vanderbeck arrived with Mahler and settled near Boise Creek.

In the years to come, many homesteaders tried to eek out a living in the Plateau wilderness. Several succeeded in establishing successful farms and mills, but others gave up their claims, overwhelmed by the difficulties faced in this remote place. John Templeton, James Shorley, Charles Clark, and Peter Sanders all filed claims and then left by 1874. Those coming later often used their abandoned cabins until more suitable living quarters could be erected.

Boise Creek

The first settler at Boise Creek area was George Vanderbeck, who accompanied Johannes Mahler to the Plateau in 1870. His wife and baby from Chicago soon joined him, to become the first white family in the area. Their claim extended to where Enumclaw High School now sits and near where an Indian longhouse was located then. A few months later, Henry Grothen and his family joined them.

James Johnson, his wife, and five of their twelve children moved from eastern Canada to a spot near the confluence of Boise Creek and the White River in 1875. After James put a cabin together, he built a flour mill and dam to power it. He also operated a ferry across the White River. This wasn't your ordinary ferry, but a small rowboat following a cable across the rapids. With no Mud Mountain Dam to control the flow, the crossing was often very dangerous. The boat often capsized, and several pioneers, including four mailmen, drowned. Horses and other animals had to swim, and many of them were lost also.

As others began moving in, George Vanderbeck anticipated that the settlement would flourish once the railroad came through, so he platted part of his homestead as a town in 1888 and established a post office the following year. His prediction came true when the Northern Pacific Railroad ran its main line through there and built a trestle across the White River bridge to Buckley. The town became a flag station, where trains stopped if the flagman raised the flag; otherwise, they passed on by. By this time, Boise Creek boasted a school, two general stores, a hotel, a sawmill, a shingle mill, and a saloon.1

The community also got a log bridge over the river, rendering the ferry obsolete. After it was destroyed by flooding in 1906 and again in 1911, a new steel bridge was built, which was also destroyed by flooding.

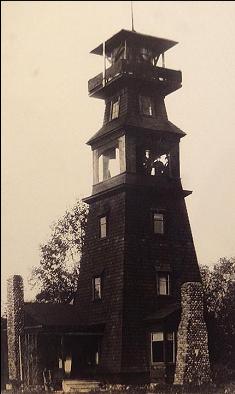

A colorful Boise Creek character was E. L. Robinson. He and his wife came there to start a utopian community. Although that venture failed, he did build Tower House, a unique residence near where Boise Creek enters the White River. Six stories high, it featured a water tower on top, an enclosed observation room on the fifth level, an open balcony below that, and living quarters on the first three floors. Robinson was a philosopher who shared his thoughts readily with anyone who would listen. A young Houston Allen was one. "Mr. Robinson was a poet, and he was rather deaf, in fact, he was extremely deaf. He taught me the deaf and dumb easy language. I talked to him with my fists and fingers enough and he would guess what I was going to say and he would beat me to it every time."2

Allen also talked about a train loaded with pigs and kegs of wine that wrecked next to Robinson's by the White River bridge. As the pigs got loose and lapped up the wine, farmers from all over the area came and tried to catch the inebriated animals.3 The Buckley Banner reported on a different aspect of the event. "A car containing forty-five barrels of wine of different kinds was almost completely telescoped by the tender of the eastbound train, and the wine flowed in streams in every direction." The reporter went on to describe many upstanding citizens from both sides of the bridge collecting (and drinking) the

Allen also talked about a train loaded with pigs and kegs of wine that wrecked next to Robinson's by the White River bridge. As the pigs got loose and lapped up the wine, farmers from all over the area came and tried to catch the inebriated animals.3 The Buckley Banner reported on a different aspect of the event. "A car containing forty-five barrels of wine of different kinds was almost completely telescoped by the tender of the eastbound train, and the wine flowed in streams in every direction." The reporter went on to describe many upstanding citizens from both sides of the bridge collecting (and drinking) the

E. L. Robinson's Tower House at Boise Creek

Mason Smith filed a claim on Porter's Prairie in 1872 and later bought out his brother-in-law's adjacent claim. With his sons, he developed a very large farm. One son, L. C. Smith, later became a County Commissioner, mayor of Auburn, and King County Sheriff, while his grandson became mayor of Seattle.

In 1874, Edwin White and his family traveled across the country from Boston to San Francisco on the new transcontinental railroad and then to Seattle by boat, by a small steamer up the Duwamish River to Slaughter (Auburn), and by George Vanderbeck's lumber wagon to Porter's Prairie. The Whites moved into a cabin abandoned by a settler who found the pioneer life here too difficult.

One of the first roads in the area was Road No. 67, (later L. C. Smith Road, now part of the current SE 456th Way). This route, which had been in use since at least 1867, provided a link to other nearby communities. Locals began building other roads, and the new wagon road from Puget Sound over the Cascades (following the native Naches Pass trail) passed through Porterville.1

In the 1890s, Osceola farmers joined the hops boom until it crashed, and the Whites, among others, lost their farm. Several of their neighbors who survived the Panic of 1892 turned to dairy and poultry. Years later, the Jokumsen family set up a large cucumber farm and opened the Osceola Pickle Company.2

The French District/Firgrove

In 1873, Basil Courville settled in what was soon to become the French area, and much later, Firgrove. The French Canadian was 63 at the time and had spent a good part of his life with the Hudson's Bay Company, but also served in the Civil War. He had previously been a pioneer in California and Oregon. Courville arrived with his full-blooded native wife, whom he had taught to speak very good French, and four children, ranging in age from eight to twenty.1

Eusebe Fournier settled nearby in 1875 but failed his claim, as did four others on the Plateau that year and one in 1876. Finally, in 1877, the Courvilles got permanent neighbors, Charles Forget and his family, along with his brother-in-law, Joe Gautier.2 They bought three cows from the government and brought them by boat to Seattle, then drove them on the trail all the way here.

The French-speaking population of the area suddenly grew from one to eight, with two additional babies the following year and two more wagons arriving with Jack Aubert and Eugene Cota's family. Aubert failed his claim, but the Cotas became lifelong residents.

In 1874, Edwin White and his family traveled across the country from Boston to San Francisco on the new transcontinental railroad and then to Seattle by boat, by a small steamer up the Duwamish River to Slaughter (Auburn), and by George Vanderbeck's lumber wagon to Porter's Prairie. The Whites moved into a cabin abandoned by a settler who found the pioneer life here too difficult.

One of the first roads in the area was Road No. 67, (later L. C. Smith Road, now part of the current SE 456th Way). This route, which had been in use since at least 1867, provided a link to other nearby communities. Locals began building other roads, and the new wagon road from Puget Sound over the Cascades (following the native Naches Pass trail) passed through Porterville.1

Porter's Prairie today

In honor of its pioneer, the settlers of the 1870s near Allen Porter's land claim called the area Porterville. By 1877, a post office was established, the community was connected with official county roads, and the name of the settlement was changed from Porterville to Osceola . In the 1890s, Osceola farmers joined the hops boom until it crashed, and the Whites, among others, lost their farm. Several of their neighbors who survived the Panic of 1892 turned to dairy and poultry. Years later, the Jokumsen family set up a large cucumber farm and opened the Osceola Pickle Company.2

The French District/Firgrove

In 1873, Basil Courville settled in what was soon to become the French area, and much later, Firgrove. The French Canadian was 63 at the time and had spent a good part of his life with the Hudson's Bay Company, but also served in the Civil War. He had previously been a pioneer in California and Oregon. Courville arrived with his full-blooded native wife, whom he had taught to speak very good French, and four children, ranging in age from eight to twenty.1

Eusebe Fournier settled nearby in 1875 but failed his claim, as did four others on the Plateau that year and one in 1876. Finally, in 1877, the Courvilles got permanent neighbors, Charles Forget and his family, along with his brother-in-law, Joe Gautier.2 They bought three cows from the government and brought them by boat to Seattle, then drove them on the trail all the way here.

The French-speaking population of the area suddenly grew from one to eight, with two additional babies the following year and two more wagons arriving with Jack Aubert and Eugene Cota's family. Aubert failed his claim, but the Cotas became lifelong residents.

precious liquid in cans, pans, buckets--anything that would hold wine. Those with no containers "would hold their mouths under the drip and guzzle like hogs under a watering trough."4

Porterville/Osceola

Porterville/Osceola